Victorian Woodcut Prints Dark Arts Corpses Skeleton Suicide in Lake

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before press.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before press.

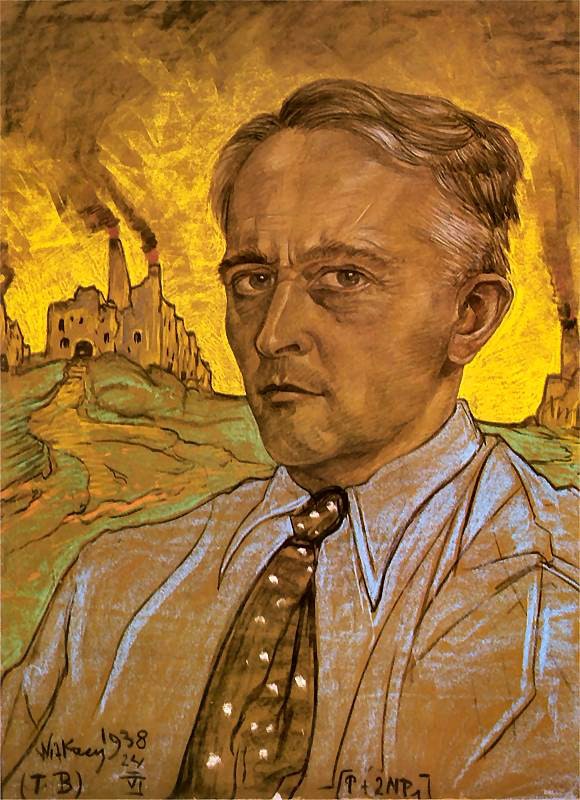

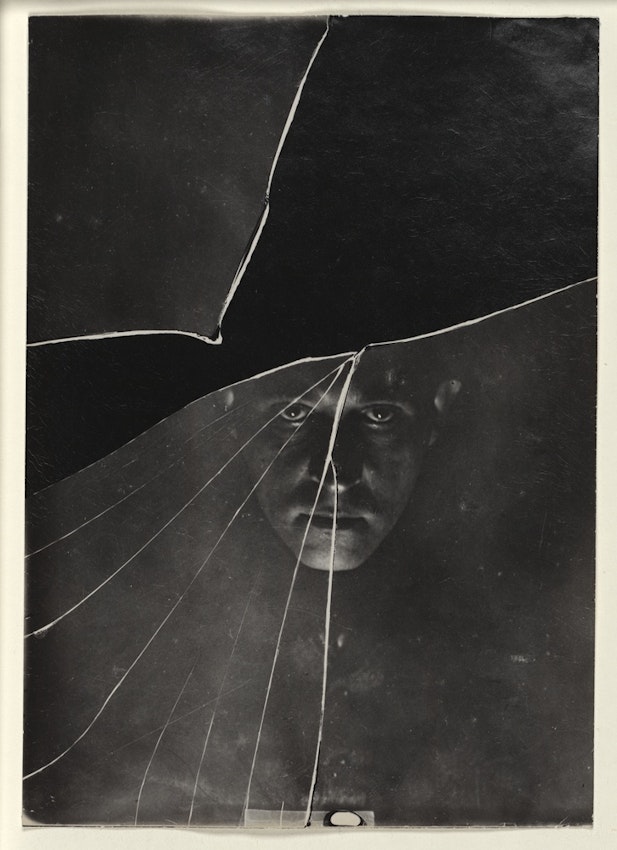

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Cocky-Portrait, 1938 — Source.

ane:52 – The visions seem to be waning.2:05 – Ages pass. Unabridged mountains, worlds, and gaggles of visions. Also many reptiles. The last one: A cavern fabricated of pigs. I'1000 in a gigantic moving pig, made of piggish tiles. Narcotics spawn styles in art and compages.

4:x – I see graphic depictions of all my flaws and mistakes.1

Perhaps it is the chief bailiwick of the self-portrait that captures your attention. Debonair in a crisp blue shirt and spotty necktie, Polish creative person, author, and philosopher Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy) strikes a archetype pose: head slightly turned abroad, steely gaze, half-grinning. Or maybe your eyes pan beyond Witkacy to the strangely apocalyptic groundwork — ruined buildings, rendered in smudged grayness and yellowish pastel, leaching smoke into the air. A prophetic vista, given that the portrait was completed in 1938. Either way, it is like shooting fish in a barrel to overlook the inscription, in the blackness crayon of Witkacy's spiky hand, jotted across the lesser of the prototype: [P + 2NP1]. It looks nearly like a signature, a cipher, or a record of ownership. This is Witkacy's formula for keeping note of the substances he had consumed during the artwork's composition, and of a previous spell of sobriety. In this example, P denotes "palenia", or smoking tobacco, while 2NP1 signals ane month and 2 days of "not-smoking".

Under the influence of cocaine, mescaline, alcohol, and other narcotic cocktails, Witkacy prepared numerous studies of clients and friends for his portrait painting company, founded in the mid-1920s; the mix of substances inducing different approaches to colour, technique, and composition. The resulting images are surreal — and occasionally horrific. Heads become disembodied busts, suspended in the night sky. Bodies are transformed into worms. Faces seep downward the paper.

Ringlet through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Ringlet through the whole page to download all images before printing.

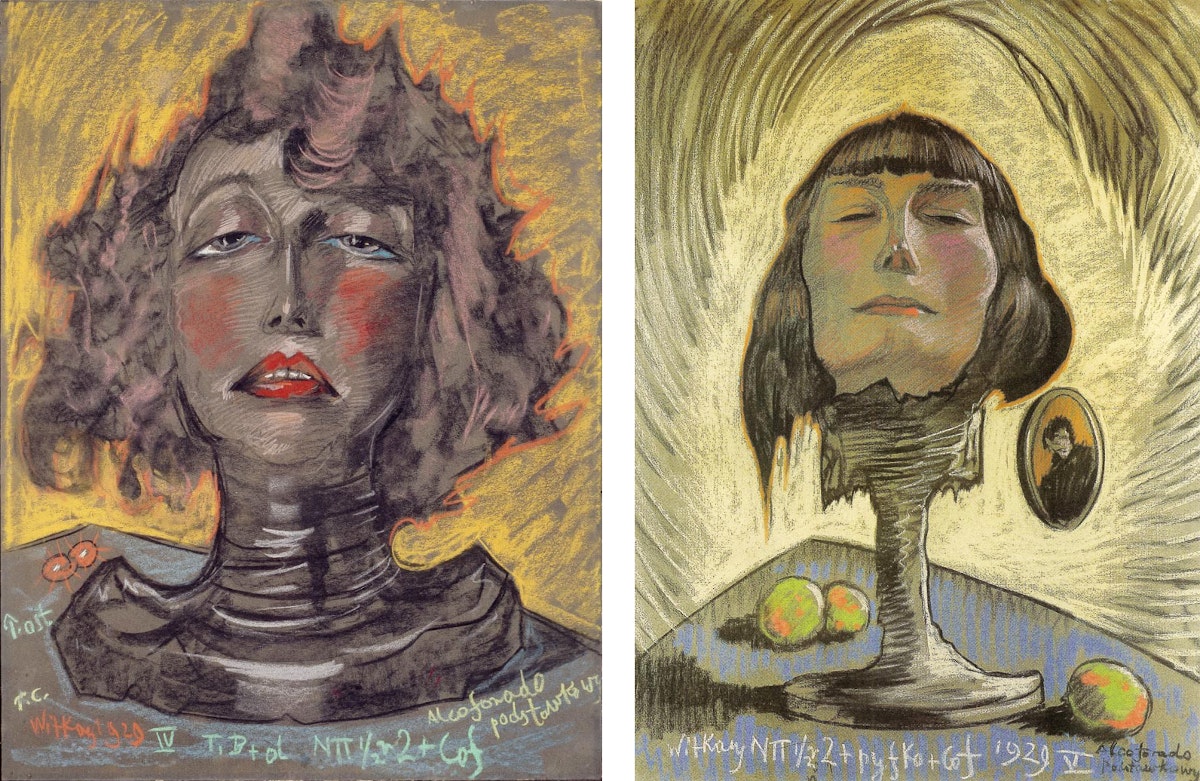

Left: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Portrait of Nena Stachurska, 1929. Blazon "B + d" portrait (a magnifying of character, retaining a prettiness exaggerated towards "demonism"). Caffeine, no alcohol. Right: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Portrait of Maria Nawrocka, 1929. Beer + caffeine — Source: left, right.

Scroll through the whole folio to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole folio to download all images before printing.

Left: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Portrait of Stefania Tuwimowa, 1929. Blazon "B + East (+A)" portrait ("the composition takes the form of a sketch", with spruced up and slick execution). Caffeine, no alcohol. Right: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Portrait of Stefan Glass, 1930. Smoking — Source: left, right.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Left: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Self-Portrait, 1918. Type "D" portrait (executed with subjective characterisation, as if under the influence of drugs, but without "recourse to any bogus means"). Right: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Portrait of Nena Stachurska, 1929. Type "C" portrait (under the influence of "narcotics of a superior grade"). Mescaline synthesised by Merck + cocaine + caffeine + cocaine + caffeine + cocaine) — Source: left, right.

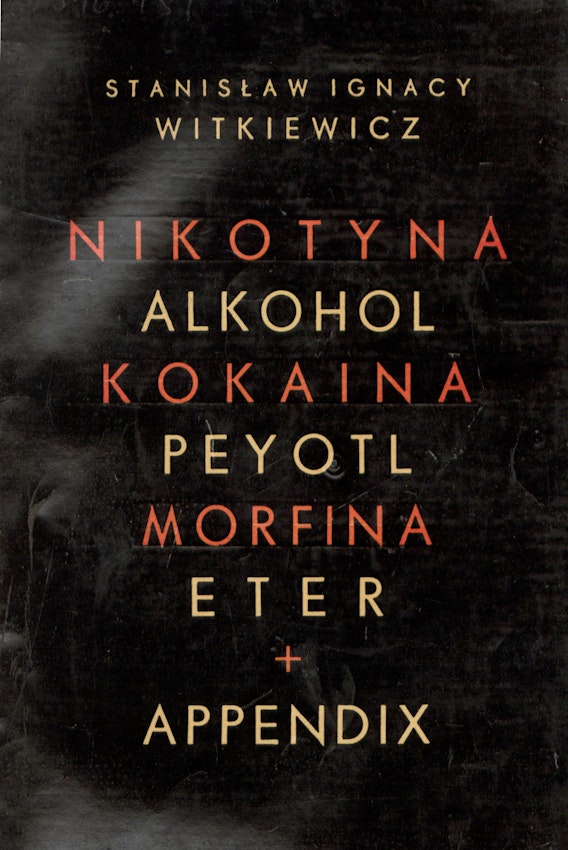

Witkacy's experimentation with drugs was non limited to the studio. In 1932, he authored Narkotyki (Narcotics), a series of essays describing his intake, alongside analysis of contemporary attitudes towards drug use. During the 1920s and 30s, substance corruption in Poland was increasingly seen equally less a medical consequence, more than of a social and even national business, perceived equally a threat facing the newly-independent Polish land. Particular criticism was levied confronting alcohol, though other drugs, including tobacco, were also criticised at times for their detrimental health furnishings.2 At first glance, Narkotyki appears to employ a similar rhetoric of abstinence. The front end cover ominously lists a roster of recreational substances, in blazing blood-red and xanthous.

Curl through the whole page to download all images before press.

Curl through the whole page to download all images before press.

Encompass of the 1932 edition of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz'southward Narcotics — Source.

In the preface, Witkacy claims he is "writing in total seriousness . . . to produce something useful"; describes how his "main aim is to salvage hereafter generations from the two most monstrous stupéfiants, tobacco and booze"; and claims substance use "ultimately atomic number 82[s] to a personality becoming entirely altered, spiritually disfigured".3 His is a "purely psychological" method, he adds.4 Information technology's a very honourable approach — but, typical Witkacy, this was all a bit of ruse.

Narkotyki owes much to the experimental works of other European psychonauts throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Witkacy's idea of drugs as being both sublime artistic fuel and a fast-track to the doldrums evokes Thomas De Quincey's opium-laced visions in his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821); his playfulness with style, reflecting the ephemeral escape offered past drug-taking — and his acknowledgement of its longer-term, more than pernicious social consequences — smacks of Charles Baudelaire's poesy and writing on hashish.5 Similar Baudelaire, Witkacy frequently situates his experiments within wider ideas virtually the function of the creative person in an increasingly modernised gild, and the possibilities opened by altering the perceptual faculties. "Every bit humanity adapts to society, to the progressive mechanization and quickening pace of life", he writes, "the artist, a specialist in channeling the immediate expression of metaphysical sensations, has had to distance himself formally from the social foundation, though information technology is where his life is rooted."6 Whatever his debts to other explorers of altered states of consciousness, Witkacy was too future looking. At certain points, he adopts a process of fourth dimension-stamping his experiences as they progress after ingestion: a method that anticipates the internet's Erowid portal — a sort of intoxicated version of the Mass Observation projection, which allows volunteers to submit public accounts of their experiences on diverse substances. And his intoxication was both physical and formal. As the translator of the 2018 English language version of Narkotyki, Soren A. Gauger, notes, Witkacy's prose is often tricksy and double-crossing: he is "exhilarating and exasperating", writes Gauger, "no matter what he was writing, it seems he wished he was writing something else".7

Born in 1885 in Warsaw, and so office of the Russian Empire, Witkacy was raised in the southern mountain resort of Zakopane — the air and spirit of which would later lead him to deem it "the master product plant of a unique, purely Shine drug, Zakopanine". His formative years were spent effectually cultural innovations, including those past his father, painter and critic Stanisław Witkiewicz, who was associated with the innovative Młoda Polska (Young Poland) Arts and crafts movement.8 Initially home-schooled, Witkacy later studied at the Kraków University of Fine Arts, debuting his paintings — Romantic depictions of landscapes which bore similarities to his father's works — in 1901. A trip to Paris in 1908 sparked an interest in avant-gardism, and he began experimenting with photography, extending lenses with the assist of drainpipes to make strange portraits. A macro focus and claustrophobic cropping brought his subjects oppressively close to the viewer; their wide-eyed and grimly-serious faces staring out of the bromide murk.9

Ringlet through the whole page to download all images earlier printing.

Ringlet through the whole page to download all images earlier printing.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz'south portrait of Tadeusz Langier, ca. 1912 — Source (CC BY-NC-SA).

Witkacy's early career was marred by tragedy. In 1914, his fiancée Jadwiga Janczewska died by suicide, sending him into a tailspin. Every bit a distraction, his babyhood friend, anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, invited him to photo an upcoming research expedition through Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) and Australia to what was and so the Territory of Papua. Information technology was a disastrous trip. En route, the pair spent most of the time in their cabin, deep in Joseph Conrad's Lord Jim; upon arrival, Witkacy's letters to his father reveal an ongoing preoccupation with thoughts of his late fiancée, in which descriptions of the environment interweave intense colour and toxicity:

The copse are covered with flowers going from cherry-red and orange vermilion to violet and lake. . . . All this causes me the almost frightful suffering and unbearable pain, since she's not alive with me. . . . Everything is toxicant which brings shut thoughts of decease. When, when volition this inhuman suffering end?10

At ane point on the trip, Witkacy held a Browning pistol to his temple for an entire night. His relationship with Malinowski prickled — the anthropologist compared it to "Nietzsche breaking with Wagner" — and Witkacy soon returned for Europe to enlist in the Russian Majestic Army, whilst Malinowski continued to the Territory of Papua.eleven The friendship betwixt the pair never fully recovered.

Drafted into the Pavlovsky Guard in 1915, Witkacy fought on the frontline of World War I in autumn of the following year — though was severely wounded, come summer, in eastern Ukraine.12 Witkacy spent the balance of the war convalescing, during which time he developed his artistic manner on an industrial scale, creating around 8 hundred works, both in painting and photography.13 1 limerick, produced in St Petersburg (then Leningrad) circa 1917, was his "Multiple Cocky-Portrait in Mirrors": an unnerving photographic portrait taken in a cogitating hall, depicting five Witkacies, dressed in military compatible, staring each other down with The Lady from Shanghai-ish paranoia.

Scroll through the whole folio to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole folio to download all images before printing.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Multiple Cocky-Portrait in Mirrors, ca. 1916 — Source.

In mid-1918, Witkacy was able to get out St Petersburg and return to Zakopane, where he began exhibiting works with the avant-garde Formist group: a Cubist-Expressionist-Futurist-folk mashup movement, where psychedelic scenes, popping with color, met more graphical, geometric designs. Around the aforementioned time, he formulated the principles of his theory of Pure Form, which stressed limerick over content, and a break away from realism, naturalism, and linear narrative. For Witkacy, artistic works served as autonomous units rather than reflective enterprises, prompting gratuitous association among viewers, untrammelled by logic or consistency.14 In a 1923 lecture, he explained:

On the stage, a man or some other animate being could commit suicide as a result of a glass of water spilling, the same brute that danced for joy over the death of his dear mother 5 minutes ago . . . . Art with a tendency towards Pure Course is something accented . . . occupying a given period of time.xv

Despite his aesthetic innovations, Witkacy's works weren't selling every bit much every bit he hoped. In 1925, he decided instead to constitute a portrait business firm and — under the motto "the customer must exist satisfied" — proposed seventeen increasingly sardonic rules, including the classification of portraits into a number of separate styles:

— Type A: "'Slick' execution, with a sure loss of grapheme in the interests of beautification, or accentuation of 'prettiness.'"— Type B: "More emphasis on character but without whatsoever trace of caricature"

— Blazon B + d: "Intensification of graphic symbol, bordering on the caricatural."

— Type C: "executed with the aid of C2H5OH [ethanol] and narcotics of a superior grade . . . . Approaches abstruse limerick, otherwise known as 'Pure Form.'"

— Type D: "The aforementioned results without recourse to whatever artificial ways."

— Type E: "Spontaneous psychological interpretation at the discretion of the House."16

Afterward in the rule-book, Witkacy added: "any sort of criticism on the role of the customer is admittedly ruled out . . . if the firm had immune itself the luxury of listening to customers' opinions, it would have long ago gone crazy." Anticipating his writing in Narkotyki, Witkacy'southward portrait painting company was less a serious enterprise than an experiment in boundary-breaking, mischief, and devilish contradiction. Thousands of images were later on produced, signed under various pseudonyms: Witkac, Witkatze, Vitecasse (French for "breaks chop-chop").17 Many of the Blazon C, mid-inebriation portraits were made at so-called "orgies" in which Witkacy experimented with drug combinations, overseen by a friend in the medical profession, Dr Białynicki-Birula.18 Rumours about these parties — and Witkacy's habitual drug-taking — abounded among the general public; even a decade later, in the tardily 1940s, Białynicki-Birula issued a letter to the press confirming their serious nature, and refuting the suggestion that Witkacy was always addicted to drugs.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

1934 photograph of Jan Kochanowski (left), Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (bottom), Roman Jasiński (peak), and Bruno Schulz (right) — Source (PD status unknown).

Curl through the whole page to download all images before press.

Curl through the whole page to download all images before press.

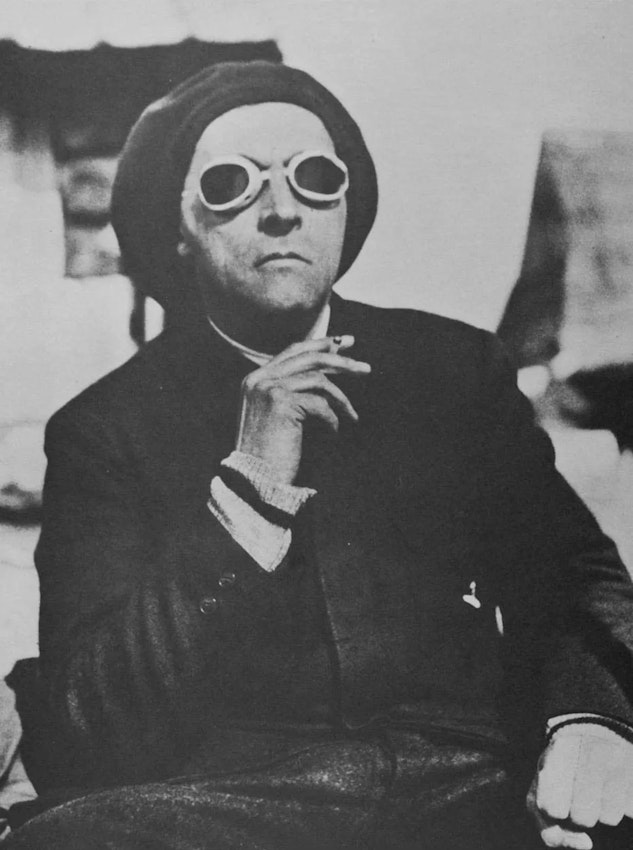

Photo of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz in ski goggles, ca. 1930s — Source (PD status unknown).

Throughout the interwar menstruation, Witkacy garnered a reputation among artistic circles equally Poland's resident eccentric. For author and playwright Witold Gombrowicz, he was: "never at rest, always highly strung, tormenting himself and others with his perpetual playacting, his craving to stupor . . . forever cruelly and painfully playing with people".19 Photographs of Witkacy are peak interwar slapstick: in one, he is irascible and grimacing; another shows him looking pensive in ski goggles; in a third, he has an arm effectually the ordinarily shy Polish-Jewish curt story writer Bruno Schulz, who has his fingers over his eyes. Witkacy also took to novel writing, composing several bizarre and impressionistic works. His debut, Farewell to Fall (1927), was to a caste inspired by his travels with Malinowski, and features a cocaine party. The side by side, Insatiability (1930), is a narcotics-fuelled and eerily prescient dystopia, narrated around the year 2000, in which Europe is overrun by war, facilitated by the hallucinogenic "Murti Bing" pills.

There'southward a psychoactive bite to much of Witkacy's work — which makes his preface to Narkotyki all the more farcical. If Witkacy was Poland'due south answer to De Quincey, so his was a more misreckoning arroyo to substance intake: one part didactic, one office satirical. "I will write the chapter on nicotine in a sorry state of withdrawal", he claims, and so adds: "of class, I might very well begin smoking again in the middle of writing . . . and so many times this has happened!"twenty Just as his innovations in the visual and literary arts embraced the eccentric and contradictory, Witkacy's nonfiction was also charged with paradox, reflecting his clashing human relationship with indulgence and withdrawal.

Curl through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Curl through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Deception of Woman, with Self-Portrait, 1927. The chemical central top left tracks 3 bouts of nicotine withdrawal and indicates the work was completed during a tobacco relapse. The portrait Witkiewicz holds bears a key for type "D" (budgeted "Pure Grade" without intoxicants) — Source.

Though written with all the fastidious limerick of a lab report, Narkotyki blends objective documentary with more than personal, somatic, and frequently hilarious explanations of Witkacy's experience on drugs, and the complexities of addiction. Drugs are a gateway "to see the world from 'the other side'" (similar language also appears in Farewell to Fall, just here they do not offer an escape from reality, instead revealing its contradictory and fickle undercurrents). Narkotyki slips from desire, greed, and vanity to disappointment and blame; from chronicles of social mores to sharpened invective; intimate reminiscences to artistic theorising.21 At one indicate, Witkacy breaks away from drug-talk to dedicate several pages to refuting supposedly serious allegations against him:

I deny having had sexual relations with my Siamese cat, Schyzia (a.k.a. Schizophrenia, Isotta, Sabina, of whom I am so fond, but nothing more), and that the mongrel kittens she bore in whatsoever way have afterwards me. . . . I deny being a braggart and a womanizer ever on the make, or having seduced the wives of other men. I deny having hiked upward to the summit of Giewont in a tuxedo (I take never even owned a tuxedo), written plays as a lark, swindled and mocked, and not knowing how to draw.22

While i of Witkacy's central ideas about fine art was a conventionalities in the growing mechanisation of the world, and the separation between artist and society, Narkotyki combines civilization, life, and psychology, exposing both individual effects and full general attitudes towards drug taking.23

The first chapter, on nicotine, begins with Leo Tolstoy and ends with existentialism — "what are a few meager puffs when nothing has any significant" — via segues from moralistic suggestions for its "absolute prohibition", to the acknowledgement of the "unadulterated bovine pleasure" of cigarettes, and of differing global smoking techniques: "we Poles, Russians and Balkaners of all stripes, to say naught of the real East, suck the foul smoke right down to our navels, poisoning ourselves some 80% more than those in the Due west".24 There are diatribes on how smoking cheapens fine art — Witkacy suggests smokers see value in the nigh "hideous literature for cretins . . . those ghastly detective novels"; how it "saps your courage", causing all manner of ghastly mental and physical symptoms.25 But cigarettes are also most-impossible to jettison. Witkacy frequently mentions the regret of the smoker, who has "squandered all his life's bright opportunities for the dreary inhalation of an inadequately toasted demon weed substance from hell". Information technology is not difficult to trace this clarification, and the careful commentary on stages of withdrawal, back to Witkacy'due south own perception of himself.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before press.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before press.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Self-Portrait, ca. 1912 — Source (CC BY-NC-SA).

Following his fiancée'due south suicide, Witkacy spent much of his life treading the edge of a breakup: some of his more individual writings express fears for the demise of individuality, or describe impending catastrophe, even suicidal ideation. But Narkotyki never reaches complete apocalyptic gloom. Witkacy's style shifts throughout: rambling, excruciating descriptions of the after-effects of abstinence are defused with impeccable comic timing:

First matter in the morning your toxin-paralyzed cells seem to revive, and not just in the brain and the nervous system, but throughout your body. You feel as though they were balls in their sockets, freshly oiled and cleaned. Of course, the first thought, or scraps of thought, you have are: "What a load of crap."

Witkacy'south take on alcohol is similarly brazen. "Alcohol is wearisome", he announces — simply so offers a thorough and effervescent clarification of its psychological impact:

Reality opens its gelatinous and reeking maw, its derisive eyes goggling with wild abandon . . . past increasing the dosage of the intoxicant you can always occasionally return to the old ecstasy and gain at least a wan simulation of life.26

His account of cocaine, meanwhile, is meticulous narcotics reportage:

We spend several hours admiring a stain on a tablecloth every bit the most beautiful thing in the world, only to subsequently fall prey to the most horrific doubts about the very essence of Existence and of life at its most beautiful and sublime.

There are also shorter sections on morphine and ether, written by Polish scientists Bohdan Filipowski and Dezydery Prokopowicz (pseudonym for Stefan Glass), who utilize a slightly more than methodological approach to drug intake.

Coil through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Coil through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Creating the World, 1921 — Source.

The fourth chapter, on peyote — a small cactus containing mescaline and other psychoactive alkaloids — is Witkacy at his most breathless. Of all the drugs listed in Narkotyki, peyote takes on a peculiarly mythical status: noting the difficulties in acquiring the substance in Europe, Witkacy explains he will be "grateful until [his] dying days" for the 7 pea-sized pills he received from Prosper Szmurło — an "authentic Mexican peyote, from the pocket-sized stocks of Dr. Osta, President of the International Lodge for Metapsychic Enquiry".27 Witkacy even notes he abstained from drinking and other intoxicants after using peyote; an astonishingly foresighted understanding of the bear on of dissimilar substances on the human being body, which prefigures present-day inquiry into the effectiveness of hallucinogens to care for alcoholism.28

The subsequent thirty pages offer an eleven-hour account of Witkacy's emotional and physical land while nether the influence of peyote: the rate of his pulse; the raging appetites; the drawings he attempts to create; his inability to slumber; and the ceaseless hallucinations (of light-green embryos every bit big as a St Bernard, of anteaters spinning backwards, of piscine cantankerous-sections — or, every bit Witkacy puts it, "giant shark common cold cuts"; of imaginary and fantastic meetings with Polish politicians; of rotting body parts; of erotica; of skiing).29 "Peyote reality", he summarises, "is like our ain seen through a microscope . . . the longer the optics are close, the more the field broadens and sometimes even 'envelops' the peyote user like everyday reality, creeping up on both sides and fifty-fifty producing the strange sensation of having eyes at the back of your caput".30

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Green Eye Composition, 1918 — Source.

Drug reality, though, comes in many forms; sometimes physical, sometimes cultural. A compulsive code-switcher, Witkacy's understanding of experimentation (with art or drugs) every bit a technique to create formal and social altitude as well includes a sensitivity to the failings of ordinary linguistic communication to capture experience. In the preface, he notes:

I hope to show you the small mental shifts that ultimately lead to a personality condign entirely altered, spiritually disfigured, devoid of Geist (the Polish discussion for "spirit," duch, does not convey the range of the German language Geist and the French esprit – knack, spark, glimmer, drive, etc.), creative power, and a striving toward the Unknown, which requires courage and a carefree mental attitude that are systematically pulverized by an odious addiction.31

Visual artworks, Witkacy'southward or otherwise, and linguistic communication — of trip the light fantastic, song, incantational poetry, and prose — tin can cause the beholder and reader to feel spiritually altered; a transposed trip, a kind of second-order intoxication, or a contact high from the creative person'due south own altered state. I think here of the whirligig beat of a waltz, and of a velvety phonation crooning among lamenting violins:

Gdy mówisz mi, że kochasz mnie

Twe słowa są, jak opjum...

(When y'all tell me you honey me

Your words are like opium…)

This is non Witkacy speaking. These are the lyrics of a mesmeric Smoothen vocal written in 1933, "Opium", which was performed in the leading cabarets of interwar Warsaw. But in many ways, the song proves Witkacy'due south point: despite official condemnation, drugs — soft and hard — were substantially intertwined with everyday civilization in the early on twentieth century, both in Poland and on a wider scale across Europe. Another case study might be found in the 1936 Smooth tango "Morfina" (or Morphine), with like lyrics, about a beguiling drug-turned-lover; or in the plethora of ad songs for cigarette companies produced in the period — like the 1937 tango "Nikotyna", the tale of a femme fatale chosen Nicotine, who turns blood to wine and drives men to despair. Additional examples would include the musical first-aid-kit of interwar Polish advertising songs for painkillers and medications; or the high-quality pictorial advertisements for pharmaceutical firms of the era, including by illustrator duo January LeWitt and George Him (who later designed wartime propaganda posters for the British war endeavor).

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Smoothen temperance posters from the 1930s warning about the effects of drinking denatured (methylated) alcohol — Source (PD condition unknown).

Narkotyki became an immediate hitting, acquiring about modernist cult status: Gauger notes that one contemporary critic suggested the book "needed no introduction because half of Poland could be seen conveying it around".32 Was this considering Witkacy's public could relate to the content? Considering he dared to toy with societal rules and authority? Or considering he left it ambiguous equally to whether the book was a serious project at all? Witkacy'south oft-overlooked appendices to Narkotyki have a commonplace focus, emphasising prosaic habits — washing, shaving, and haemorrhoid care — sometimes with recommendations for treatment, and sometimes highly-seasoned to readers directly. Peradventure this was why his works gripped audiences. Witkacy always skated the thin line between relatability and absurdity; betwixt the educational and the visceral; between life and art.

Witkacy's fate, though, was decidedly more grim. Afterwards Germany invaded Poland in 1939, he fled east to Jeziory with his lover, Czesława Oknińska. Seventeen days later, Soviet forces too invaded the country — and Witkacy committed suicide. After the state of war, his sealed coffin was moved and reburied in Zakopane; several years later, Polish authorities re-exhumed his remains, and opened the coffin.

Then came Witkacy's final joke, which could have been plucked straight out of his narcotic-induced hallucinations.

Juliette Bretan is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, researching Anglophone and Polish literature of the early 20th century. She has previously featured on the BBC Earth Service, and written for the Sunday Times, The Independent, Euronews, and CultureTrip about Polish culture (especially of the interwar period) and current affairs.

beattielabody1966.blogspot.com

Source: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/documenting-drugs/

0 Response to "Victorian Woodcut Prints Dark Arts Corpses Skeleton Suicide in Lake"

Post a Comment